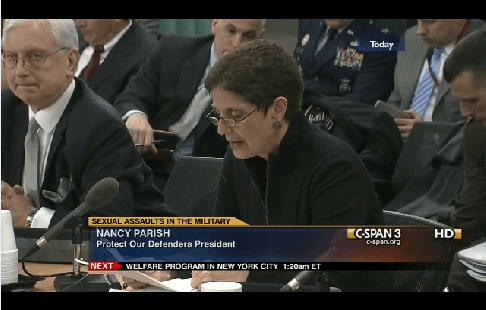

Watch Nancy Parrish on C-SPAN: Click here to watch recorded video

January 11, 2013

Secretary Panetta is correct in stating that unpunished sexual assault in our military is an epidemic. It has been for decades and continues to undermine mission readiness and unit cohesion. Although the military has taken action, it is important to acknowledge that these actions have not resulted in a reduction in the scope of the problem. Sexual assault in our military has a deeply rooted cultural component and until prosecutions increase dramatically, the culture that allows this problem to continue will persist.

The recent wars may have exacerbated this crisis, but this epidemic predated the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the increase in women in the military. Men are in the majority of the estimated half a million veteran victims. This is about the Department of Defense’s abject failure to protect the rights of service members and frequent cases where victims are unjustly treated and even overtly attacked by those in command — in a manner that is effectively countenanced by the Department.

Protect Our Defenders was founded as a place for survivors to build community, amplify their voices, support one another, provide services and collectively take action on behalf of veterans and active service members who have been treated unjustly. I’m here to represent the voice of survivors. Since I’m not one myself, I think it’s important for you to, in some way, hear their voices.

Sgt. Smith’s Story – A Culture of Harassment, Misogyny and Assault

Three months ago, Air Force Sergeant Jennifer Smith, who loves the military and is honorably serving our country, went public with an official complaint of allegations of harassment and sexual assault.

Sergeant Smith has had several tours of duty including Iraq, earning achievement medals and stellar performance reviews. But, for seventeen years, under a number of commanders and on several bases, she endured what thousands of service members endure every day: an environment of hate speech; inappropriate or violent gender-based, degrading behavior; bullying; and sexual assault. And, like so many others, she has done everything in her power to protect herself and her career. Eventually, she sought help from her chain of command – none was forthcoming.

This is not just about simple pinups. It is about formal traditions – hate filled documents, images, songs, and practices. Coins [See Exhibit G] printed, according to the Smith complaint, at government expense depicting women as objects of ridicule and exploitation, and voluminous misogynist materials on government servers. It is about impressionable seventeen and eighteen year old female trainees forced to walk into mess halls and face something called a “Catwalk,” which consists of demeaning organized shout outs about their gender and their bodies. Female Marines are called upon to repeat cadences that humiliate and objectify them. Sergeant Smith was forcibly carried into a bar, in what is known as a “sweep,” physically thrown on the counter, and forced to endure a “naming ceremony,” which involves officers loudly singing songs with graphic descriptions of women being mutilated and sexually violated. A phrase from one such songbook [See Exhibit M] goes like this:

“who can take two ice picks, stick’em in her ears ride her like a Harley while you f**k her in the rear. Who can take a chainsaw, cut the bitch in two, this half is for me, the other half is for you.”

Officers themselves describe, in a handbook of Air Force traditions, that, because they take risks and do things that are hard and dangerous, it is therefore ok for them to denigrate and even abuse others, who in their view are less worthy. And, as an officer with sixteen years of service recently described to me: upon arriving at a particular base overseas she was alerted by another female officer that, “almost every woman carries a knife and so should you, not for battle against the enemy, but to cut the person who tries to rape you.”

In response to news coverage of Technical Sergeant Smith’s formal complaint, Air Force Chief of Staff General Mark Welsh ordered a service wide sweep of workspaces and public areas for images, calendars and other materials that objectify women. The sweep, which, after a prior public announcement, began on Wednesday, December 5, 2012, provided a twelve-day window for it to be completed. This window and public notification intentionally or unintentionally provided service members the time to hide the content, and the opportunity for commanding officers to not find anything. The sweep was executed by commanding officers who had an incentive not to find anything that would reflect poorly on the command climate they are charged with maintaining. This sweep also did not include individual desks, cabinets, lockers, or military issued computer hard drives, where much of the content in the Smith complaint was stored.

Servicewomen are much more likely to be assaulted in the military than are women in civilian life. According to The New York Times, it is estimated that 17% of women in the general population become sexual assault victims during their lifetime. While a 2006 VA study estimates that 22% – 33% of female service members are assaulted while in the service.

Male rape and assault victims face severe isolation and disbelief. According to survivors, many are gang raped and then ridiculed for coming forward. Their assault is often chalked up to hazing. When survivor, Heath Phillips reported being repeatedly gang raped, he was called a liar and a mama’s boy. To avoid the continual brutal attacks onboard his ship, Heath left and was charged with going AWOL. According to DoD [PDF] out of the estimated 19,000 assaults that take place annually, 10,000 are men.

Long Existing Problem

This is not a new problem or a recent revelation. More than 20 years ago, during the Tailhook scandal, the Navy said all the right things about confronting the problem, but fundamentally nothing changed. In Sept. 1992, according to an LA Times story, Acting Navy Secretary Sean O’Keefe said:

“We get it. We know that the larger issue is a cultural problem, which has allowed demeaning behavior and attitudes towards women to exist within the Navy Department. Our senior leadership is totally committed to confronting this problem… Those who don’t get the message will be driven from our ranks.”

Now 20 years later, faced with another scandal, Air Force Chief of Staff General Mark Welsh’s recent words are eerily similar when he said:

“In my view, all this stuff is connected. If we’re going to get serious about things like sexual assault, we have to get serious about an environment that could lead to sexual harassment some ways, this stuff can all be linked.”

Words matter, but only if they are followed with fundamental legislative reform and culture changing action.

Scandals, Reports, Reforms – 25 Years and Counting

For over 25 years, scandals of sexual violence within the military, cover up and abuse of authority have come to light, often due to brave service members, who risk their careers and wellbeing by coming forward. This includes Tailhook in 1992, Aberdeen Proving Ground in 1996, the Air Force Academy in 2002, USMC Marine Barracks One, Washington in 2012 and the ongoing largest military sexual abuse scandal in history at Lackland Air Force Base. Military leadership has repeatedly investigated itself, punished well-publicized offenders, and released reports touting supposedly new reforms that have not and will not fundamentally fix the broken system.

The Tailhook scandal investigation, in 1992, (where 83 women and 7 men were groped and assaulted) was going nowhere, until former Navy pilot, Lieutenant Paula Coughlin stepped forward. The subsequent reports and reforms failed to produce a change in the culture, improve outcomes for victims or increase conviction rates.

Ten years later, in 2002 during the Air Force Academy abuse scandal, an Air Force Academy Command Survey revealed that 63% of female respondents said they were the subject of derogatory comments based on their gender and 57% felt generally discriminated against.

The 2010 and 2011 DoD and SAPRO reports [PDF] and gender surveys clearly demonstrate that the crisis persists. Although the Pentagon chose to emphasize one minor ripple in the 2011 data that could be considered an improvement: the 10% increase in the percentage of sexual assault related charges that resulted in court-martial trials. In reality: charges have decreased, initiated courts-martial fell and convictions plummeted. By the numbers: In 2010, 1,025 actions were taken by commanders on the grounds of sexual assault, in 2011 there were 791 – a decrease of 23%. The numbers of initiated courts-martial fell 8%, from 529 in 2010 to 489 in 2011. The number of perpetrators convicted of committing a sexual assault decreased 22%, from 245 in 2010 to 191 in 2011.

On June 22, 2012, twenty years after Tailhook there were momentary hopeful signs that the Air Force was taking a holistic approach in investigating the culture and ongoing scandal at Lackland. Major General Edward Rice, commander of the Air Education and Training Command, on ordering the investigation at Lackland and “all training units,” rightfully said, “it’s important to look even deeper and wider to identify any systemic issues that may place our youngest airmen at risk in any basic and technical training environment.” Unfortunately, a few weeks later without benefit of an investigation, General Rice changed his position, when on July 17th he said, “it is not an issue of an endemic problem throughout basic military training…it’s more localized, and we are doing a very intensive investigation on that squadron.”

On November 14, 2012 the Air Force released its’ internal investigation on the abuse scandal at Lackland. The report found weaknesses in institutional safeguards and leadership. The investigation did not include, as it should have, interviewing the victims of the crimes they were aiming to address. The reforms proposed are similar to the obviously ineffective reforms that other branches have taken over the past 25 years following previous public sexual abuse scandals.

On December 21, 2012 the Pentagon, in releasing the required annual “Academic Program Year 2011-12 Report on Sexual Harassment and Violence at the Military Service Academies” Secretary Panetta stated, “despite our considerable efforts, I am concerned we have not achieved greater progress, therefore I am directing that you enhance your programs. The goal is to change the culture.”

The Conflicted And Broken Justice System

The culture is a real problem, but as important — is the broken military justice system. Every aspect, from prevention and victim care, to investigation, prosecution, and adjudication is fundamentally dysfunctional and there has been no coherent effort to fix the deficiencies.

As one survivor of rape at Lackland told us, “the way all sex assault reports are handled encourages the ouster and fall from grace for almost every victim. Therefore, while on the surface it may seem as if good order and discipline exists, in reality it does not. It is quick removal of the victims through errant mental health diagnosis, legal crisis, and so called ongoing disciplinary problems: an effort to prove the victim a liar or mentally unbalanced.” The result is too often the destruction of the victim’s reputation and wellbeing.

The inconsistencies and conflicts inherent in the system coupled with absolute command discretion often effectively preclude justice. It is a system that elevates an individual commander’s authority and discretion over the rule of law. It is fraught with inherent personal bias, conflicts of interest, abuse of authority and too often a low regard for the victim. Throughout, the commander impacts the legal and investigative processes and paths these cases take. The JAGs and investigators work for and answer to the commander. This process is also encumbered with inexperienced and undertrained staff, constant turnover, arbitrary and inconsistent application of the law, no sentencing minimums or guidelines, and a biased system. Article 32 preliminary hearings, which can become a black hole, down which the government’s case is lost. These hearings often are a defense free-for-all where the rules of evidence don’t apply and hours can be spent tying a victim in knots in an effort to create impeachable material for trial. It is arguably more traumatic than trial itself. The military appellate courts are highly defense protective. All of this often renders the few victims rights that exist ineffectual.

Often the command, the convening authority, is conflicted. This individual can select members of the court-martial or unilaterally and arbitrarily decide to not even move forward with one. As the convening authority for courts-martial, the accused’s commanding officer controls the decision on whether to send the case to trial, to settle at non-judicial punishment, or to ignore the allegations altogether. These convening authorities are normally military commanders and are not attorneys or judges. Though they take advice from JAGC officers, it is ultimately the convening authority’s decision on how to proceed.

The military insists absolute command discretion is required to maintain good order, discipline, mission readiness, and unit cohesion. Yet, when victims are punished and perpetrators go free and everyone knows it to be the case, trust, the essential ingredient to an effective, functioning military, is undermined. And for more than an estimated a half million service members, this system has failed to provide simple justice. All too often, the go-to-solution for the command is to eliminate the problem by sweeping the offense under the rug and kicking the victim out of the service. Whether it is personal guilt, bias, inexperience, concern for negative career repercussions or desire to quickly get back to the business at hand, the effect is the same.

The commander is also the disposing authority. The quest for a quick resolution or an affinity for the defendant sometimes leads the command to reduce sentences, grant clemency, and overturn convictions.

Furthermore, commanders are just as capable of bad behavior. Take for example, Brigadier General Jeffrey Sinclair who was recently charged with forcible sodomy among other sex offenses. An attorney, Susan Burke who has represented numerous victims stated, “In the past 27 years, how many cases could Sinclair have been able to shut down? It’s very troubling.”

Thirty-nine percent of women victims report that the perpetrator was a military person of higher rank and 23% indicated the offender was someone in their chain of command.

Reforms To Date Have Not Been Enough

2012 brought persistent and unprecedented public attention to this issue. In response to each wave of publicity, the Pentagon churned out a list of supposedly new, but, in fact, mostly recycled and historically ineffective reforms or policies.

While well intentioned, some policies place the burden on potential victims The Wingman or battle buddy policy, which requires trainees of both genders to be accompanied at all times. The way it is structured becomes a vehicle for holding victims accountable for having been attacked. Sergeant Smith, who had gone to the gym alone to exercise, was assaulted. She did not report the assault at the time, because according to her complaint, “she knew that the Air Force would blame her, the victim, and reprimand her for not having a “battle buddy” with her at all times.” We often hear similar reports from other survivors.

The most publicized reforms announced by the Secretary of Defense last year include: (1) creating a special victims unit, something the Army instituted over a year ago, without a resulting increase in cases brought forward, conviction rates or improvement in victim treatment, (2) establishing sexual assault databases, which Congress mandated years ago and which have still not been instituted and (3) moving the authority to deal with these cases up the chain of command, perhaps of some value, but the Army instituted this practice over a year ago with no discernable effect. And, other branches have also instituted this practice to some degree with little results to show for it. We also know commanders at all levels too often sweep offenses under the rug.

It’s important to note that we receive reports of well-intentioned commanders who are trying to do the right thing, but are being thwarted by uncooperative higher-ranking commanders to whom they report.

Pentagon’s Words Do Not Comport with Actions

Despite Secretary Panetta’s often-quoted declaration that there is a policy of “zero tolerance,” recent DoD actions challenge that notion.

In December 2011, a federal judge dismissed a class action lawsuit (Cioca v. Rumsfeld) filed by 28 current and former service members for sexual assaults and the ensuing retaliation suffered at the hands of the military command. He agreed with the military defense attorneys’ argument that, among other things “the alleged harms are incident to plaintiffs’ military service.” In other words, DoD argued that sexual assault and rape are occupational hazards.

Last year, Secretary Panetta opined that the core of the problem is a lack of convictions, which he says, “must be improved.” Yet in September 2012, the Secretary sent to the President an amendment to 412 – Military Rules of Evidence. The proposed Executive Order, as submitted by the Secretary, would effectively eliminate the Military Rape Shield Rule. As it stands now, MRE 412 is already too broadly construed in favor of the accused. This amendment would effectively eviscerate the victim’s privacy and further discourage them from reporting the crime.

Many Congressional Reforms are Inconsistently Applied, Unnecessarily Encumbered, or Not Implemented

Even limited reforms passed by Congress to address this crisis, are sometimes not implemented by the DoD or if promulgated, they are inconsistently applied or encumbered with requirements that often render the policies ineffective.

Language contained in the STRONG Act was folded into the 2012 NDAA and passed by Congress requiring (if requested) a victim be given an expedited transfer away from the perpetrator unless a general or flag officer disapproves. Frequently victims are told that their papers are lost, they don’t qualify, or are placed on “med-hold” under false pretenses, thereby requiring them to stay put. Protect Our Defenders recently paid for a civilian attorney to handle an appeal of one such victim and after eight months of numerous requests for an expedited transfer, it required action by three members of congress to get this young service member moved.

Restricted reports were legislated, with the hope that more victims would come forward confidentially to receive needed medical and psychological care. No criminal investigation is initiated and no perpetrator is named. Far too often, we have been told that confidentiality is not maintained; the victim does not receive adequate support or care and is still subject to retaliation; and of course the unintended consequence is that perpetrators remain free to repeat the crime. Sixty percent of women and thirty-six percent of men cited confidentiality as a reason not to report, as indicated in the 2010 SAPRO report (page 44) [PDF].

According to victims and their families, victims’ confidential communications with psychotherapists and other medical personnel and their medical records are often inappropriately disclosed. Their right to legal counsel provided by S1565b passed by Congress December 31, 2011 (NDAA 2012) was intended to provide legal assistance to sexual assault victims to protect their privacy and privileges in courts-martial proceedings. But, currently S1565b is being misinterpreted and some JAGS are refusing to provide assistance to help victims protect their privacy rights that civilians are given under HIPPA. We understand the Air Force intends to correct this and provide legal assistance to victims to protect their privacy, but there is push back from other services. It has even been alleged that the law was only intended to assist the victim in writing the rapist out of their will or to break a lease to allow a victim to move away from the rapist. This is clearly not what congress intended.

Reporting, whether restricted or unrestricted, to the unit chain of command is problematic. As one victim told us, “Another one of the biggest reasons for people not reporting, or I should say people wanting to report an assault but the chain of command blackmails them not to, is using something that the victim was doing against them…I find it hard to understand how a 20 year old should get in trouble for underage drinking because she was raped…”

Impact on Victims

The hardest calls we receive are from recently involuntarily discharged service members, such as a former airman, who was assaulted by someone in her chain of command, who said, “I still cannot grasp what happened to me. When (assaults are) mentioned to commanders, leaders and peers nothing is done about it, your report gets lost and people turn their backs on you. (For ten years,) I was honored to wear the uniform and it’s difficult for me to know that this part of me was taken away. I was treated like a second-class citizen.”

The processes and procedures are inconsistent and confusing and are often calculated to terrorize and silence the victim, to push them to and even beyond the edge of sanity.

Victims have limited resources and few places to turn. Coordinators of the Sexual Response Program and Victim Advocates throughout the military are supposed to be the “first responders.” Until recently, the Army’s SHARP (Sexual Harassment/Assault Response) coordinators were usually trained civilians, which significantly reduced the opportunity for command influence. Today, the coordinators are often active duty personnel, assigned the task as a temporary collateral duty.

And the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO) programs have been defensive and ineffectual. The office has been much criticized for its’ prevention campaigns rooted in a wrong headed 1950’s paradigm of two people getting together and making bad decisions such as the “Ask Her When She’s Sober” campaign or the “Buddy Program,” which puts the responsibility squarely on the victim. And former SAPRO Director, General Hertzog’s pledge to provide, “more outreach and support for victims,” is still undefined and victims and family members tell us calls to SAPRO go unanswered or are referred to a suicide hotline.

Victims know they put their career at risk if they come forward so 86 percent of them do not [PDF].

Of the many service members kicked out simply because they were victims of sexual violence, there are too many examples of military separation with errant medical diagnoses, such as personality disorder, or false charges, such as misconduct or moral and professional dereliction. These instances are the result of abuse of authority, pure and simple. It is an easy way out for a command that is conflicted personally or professionally and just wants the problem to go away. Since victim support, investigative, prosecutorial, and judicial personnel are generally responsible to the command structure, there are many ways for them to get the message and make the problem go away.

DoD Inappropriately Diagnoses and Discharges Victims

According to the Veterans Services Clinic at Yale Law School, since 2001, more than 31,000 service members have been discharged, many inappropriately, with a Personality Disorder (PD) diagnosis. In 2006, the Air Force diagnosed Personality Disorders among its population at double the frequency of the civilian population. And an internal DoD review concluded in 2008-09 that 91% were not processed properly [PDF].

The impact of a Personality Disorder diagnosis is devastating for our veterans. It follows them for years, as they try to put their lives back together and find new careers. Lives are unnecessarily destroyed and, to compound the injustice, a diagnosis of PD, because by definition it is a pre-existing condition, from prior to joining the service, it leaves many victims without veterans’ benefits.

Furthermore, those service members and veterans who are diagnosed with PTSD due to MST often loose their eligibility for security clearances, effectively limiting their military and future civilian employment opportunities. Yet, those diagnosed with PTSD due to combat are not similarly affected.

Military Sexual Trauma (MST) has a debilitating effect on hundreds of thousands of our nation’s veterans, who therefore face severe obstacles as they reenter civilian life. VA clinics have few resources specifically designed for these veterans, particularly for the men, who therefore often must go to women’s health clinics for help. The VA reports 40% of those female homeless veterans and 3.2% of male homeless veterans [PDF, See Page 9] who are VHA users, suffer from MST.

We often hear from survivors that the retribution, rejection, and then eviction from what they had come to regard as their military family can be as traumatic as the assault

What Happens To The Perpetrators?

Perpetrators know the likelihood is that they will continue their career with little risk of being caught, much less punished. They often become very skilled serial predators, with many victims, as they rise through the ranks. And they become skilled at currying favor with their superiors and colleagues, effectively hiding their dark side. In the 2011 DoD report out of 2,400 reported assaults – only eight percent resulted in courts-martial conviction. And, of the few convicted, many are for lesser charges, such as indecent language or adultery, and some are given light or non-judicial punishment, such as restriction to base or extra duty. The consequence is that serial predators are often permitted to leave the service, without being placed on a sex offender database.

Former US Marine Lt. Ariana Klay puts face to this abysmal statistic. According to Klay, a fellow Marine and his friend raped her. One of her perpetrators was among the 191 (the eight percent in the 2011 report) that were “convicted.” A three star general reduced his 45-day sentence, for adultery and indecent language, to seven days. The alleged rapist was paid $7,000 a month while incarcerated and no mark was left on his permanent record. The second perpetrator was granted complete immunity to testify against Lt. Klay.

The Military has Effectively Addressed Systemic Challenges in the Past

The military has effectively addressed previous seemingly intractable systemic challenges, which adversely affected its mission readiness and unit cohesion. Racism within the military was effectively addressed after the passage of sweeping transformative legislation, the Civil Rights Act, and a subsequent decision within the military that racism was a fundamental problem affecting our national security and a recognition that it was vital that the culture change. According to news reports, after the passage of the legislation, leaders like Adm. Zumwalt, “created stiff new rules against racial bias and ordered senior officers to uphold them or be dismissed.” Racism is still an issue, as is the acceptance of homosexuals in the military, but great strides have been made. Eliminating sexually oriented bullying; discrimination, abuse, and assault would enhance mission readiness and unit cohesion. Fundamental reform is necessary and can be accomplished with the right policies and the will of our military leadership.

Conclusion

The Department of Defense is responsible for failing to effectively govern its personnel. The problems are so long standing and pervasive that, at a minimum, they constitute gross negligence on the part of the leadership and actually reflect, albeit informal, countenancing of the violation of the rights of women in the service and of victims of assault, men and women. Congress, DoD, the Executive, and the Judiciary each have roles to play in righting this horrible situation.

DoD is unjustly punishing these veterans and active duty members, seeking retribution, ruining their careers, and stripping them of their rights to benefits.

In September 1992, according to the LA Times, “several lawmakers” in response to the Tailhook scandal “proposed stripping the armed services of their role in probing sexual molestation cases,” the patience and deference that congress and the American public have shown the Defense Department, in giving it the opportunity to fix this problem has come at great cost to our service members, veterans and ultimately to our society.

This crisis cannot be effectively addressed incrementally. Regardless of the reason, the chain of command is not making the right calls with these cases. Continued lack of efficacy validates the standing up of an impartial, expert office to determine effective investigation and appropriate adjudication of sexual assault cases.

We agree with former U.S. Army Brigadier General Loree Sutton when she said that it’s time to create, “an independent special victims unit completely outside the unit chain of command, under civilian oversight.”